Wild boars provide archaeologists with clues to early domestication

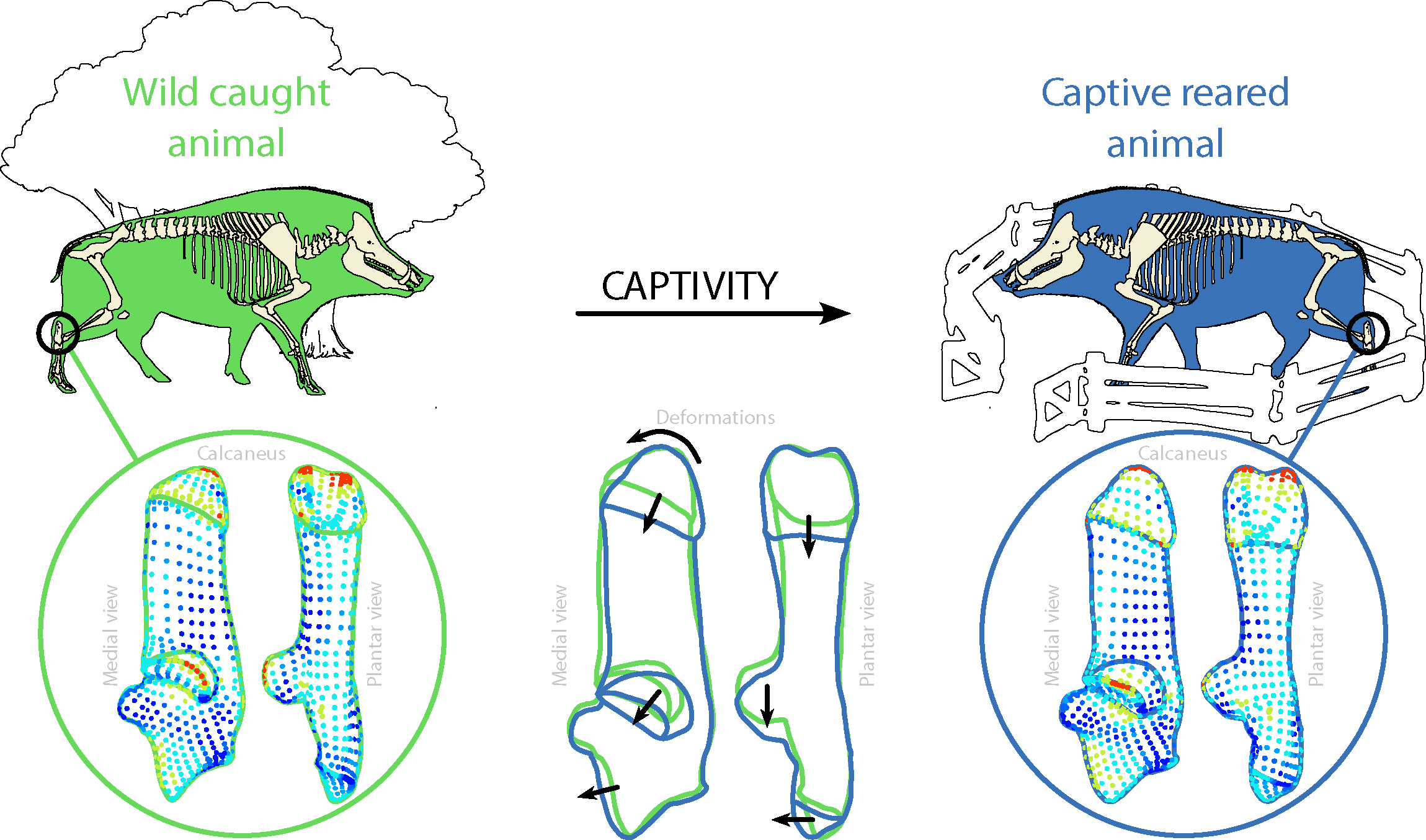

Until now, archaeozoologists have been unable to reconstruct the earliest stages of domestication: the process of placing wild animals in captivity remained beyond their methodological reach1 . Using the wild boar as an experimental model, a multidisciplinary team made up of scientists from the CNRS and the French National Museum of Natural History2 have shown that a life spent in captivity has an identifiable effect on the shape of the calcaneus, a tarsal bone that plays a propulsive role in locomotion. Being relatively compact, this bone is well preserved in archaeological contexts, which makes it possible to obtain information about the earliest placing of wild animals in captivity. This modification is caused by changes in the animal’s lifestyle, since the bone is reshaped as a result of its movement, the terrain, and muscle stress. The scientists observed that the shape of the calcaneus was mainly modified in the area of muscle insertions: contrary to what might be expected, captive wild boars displayed greater muscle force than wild boars in their natural environment. It appears that a captive lifestyle turned them from “long-distance runners” into ”bodybuilders”’. As well as providing archaeologists with a new methodology, these findings show the speed with which morphological changes can occur when an animal is taken out of its natural environment by humans, and could prove useful in programmes reintroducing captive-bred animals into the wild. These results are published in the journal Royal Society Open Science dated March 4, 2020.

The coloured dots indicate the degree of deformation (minimum in dark blue, maximum in red). The deformations are mainly related to an elongation of the muscle insertion area in the highest part of the bone.

© Hugo Harbers / AAPSE / CNRS-MNHN

- 1Genetic modifications, as well as morphological traits common to domestic animals, such as reduced size, slenderness, etc, appear after many generations, as a result of behavioural or breeding selection for traits valuable to humans

- 2This study primarily involved the following laboratories: Archéozoologie, archéobotanique : sociétés, pratiques et environnements (CNRS/MNHN), Réserve zoologique de la Haute Touche (MNHN), Adaptative mechanisms and evolution (CNRS/MNHN), Institut de systématique, évolution, biodiversité (CNRS/MNHN/Sorbonne Université/EPHE).

The mark of captivity: plastic responses in the ankle bone of a wild ungulate (Sus scrofa), Hugo Harbers, Dimitri Neaux, Katia Ortiz, Barbara Blanc, Flavie Laurens, Isabelle Baly, Cécile Callou, Renate Schafberg, Ashleigh Haruda, François Lecompte, François Casabianca, Jacqueline Studer, Sabrina Renaud, Raphael Cornette, Yann Locatelli, Jean-Denis Vigne, Anthony Herrel, Thomas Cucchi. Royal Society Open Science, 4 March 2020. DOI: 10.1098/rsos.192039