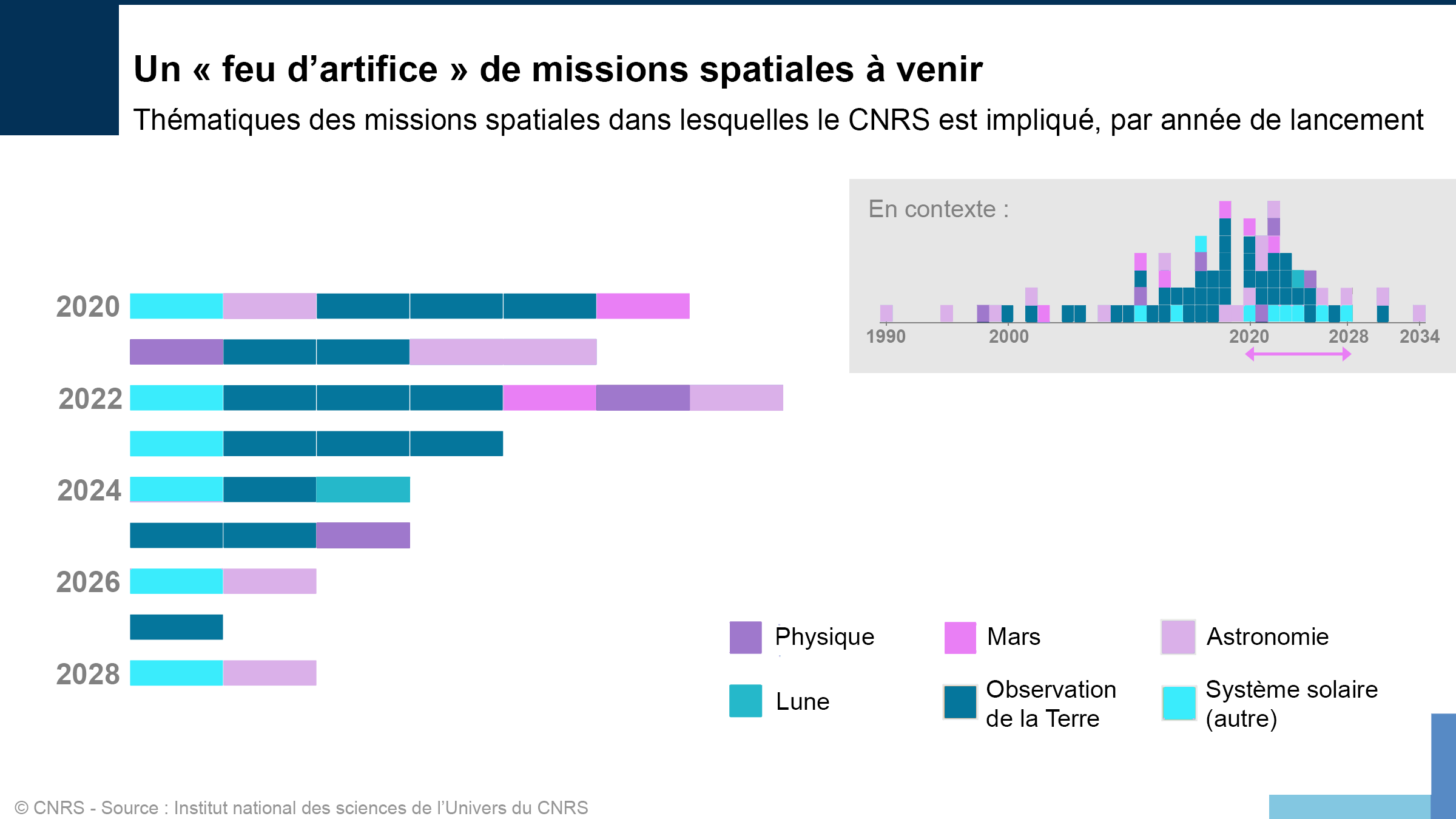

The CNRS is defending the future of astronomy to the European Union

The European Commission's recent work on new space legislation is an opportunity for the CNRS to defend the importance of preserving space research at a time when new threats are arising because of the multiplication of orbital objects.

It has been customary since ancient times to call groups of stars visible to the naked eye from Earth 'constellations', using names evoking animals or mythological figures. Will the meaning of this word change now that other sorts of 'constellations' are multiplying? These are made up of thousands of commercial satellites that continue to proliferate in the Earth's orbit to the extent that they could hinder the work of astronomists.

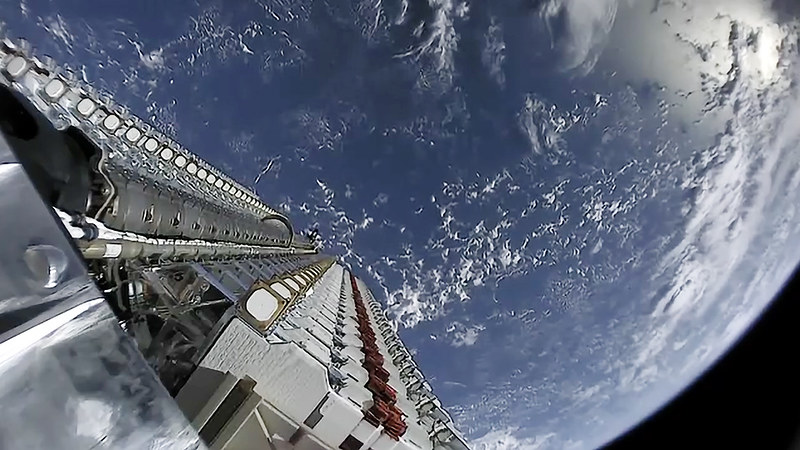

This extraterrestrial environment is increasingly being taken over by what is known as the New Space. This involves the arrival of newer and notably private sector stakeholders including the SpaceX company owned by the American billionaire Elon Musk, and its constellation of Starlink satellites. The increased risks to the cyber security of European satellites in orbit are also of concern.

The President of the European Commission clearly had this situation in mind when she called for an EU Space Law in her 'State of the Union' speech in September 2023. The objective is to position the EU as a regulatory power in this new market and also as the guardian of a 'sustainable and resilient space'. The draft law was initiated by Thierry Breton, the former Commissioner with responsibility for defence and space matters and is now waiting on the desk of his successor Andrius Kubilius whose appointment is to be validated in the coming weeks by the European Parliament.

The CNRS has taken advantage of this regulatory initiative to defend the interests of research affected by this congestion in space and has published a positioning document aimed at European regulators. The organisation's Brussels office led the project to draft this document in consultation with the CNRS Institutes concerned. The paper calls for "strong support for research and development activities, particularly through developing data production and control capacities [...], and for basic research as vectors for strong European leadership on the international stage".

Preserving research activities in space

Since 2021 the number of satellites in orbit has grown considerably. In 2023, there were close to 2900 satellites in orbit above us which is a 17% increase on 2022's figure with these representing a total mass of over 1,500 tonnes. SpaceX is literally the major player in this field with a virtual monopoly. With its constellation of 2500 Starlink satellites providing Internet access, SpaceX accounts for over 85% of the total mass of satellites in orbit worldwide and 88% of the total number of satellites put into orbit. This mass is likely to grow considerably in the next few years because SpaceX aims to send up to 42,000 Starlink satellites into orbit while other companies are also planning to launch their own 'constellations'. For example, in October 2023 the e-commerce giant Amazon sent two prototypes of its Kuiper satellites into orbit. Nicolas Arnaud, the director CNRS Earth & Space, considers the situation to be like "a jungle in which anything goes".

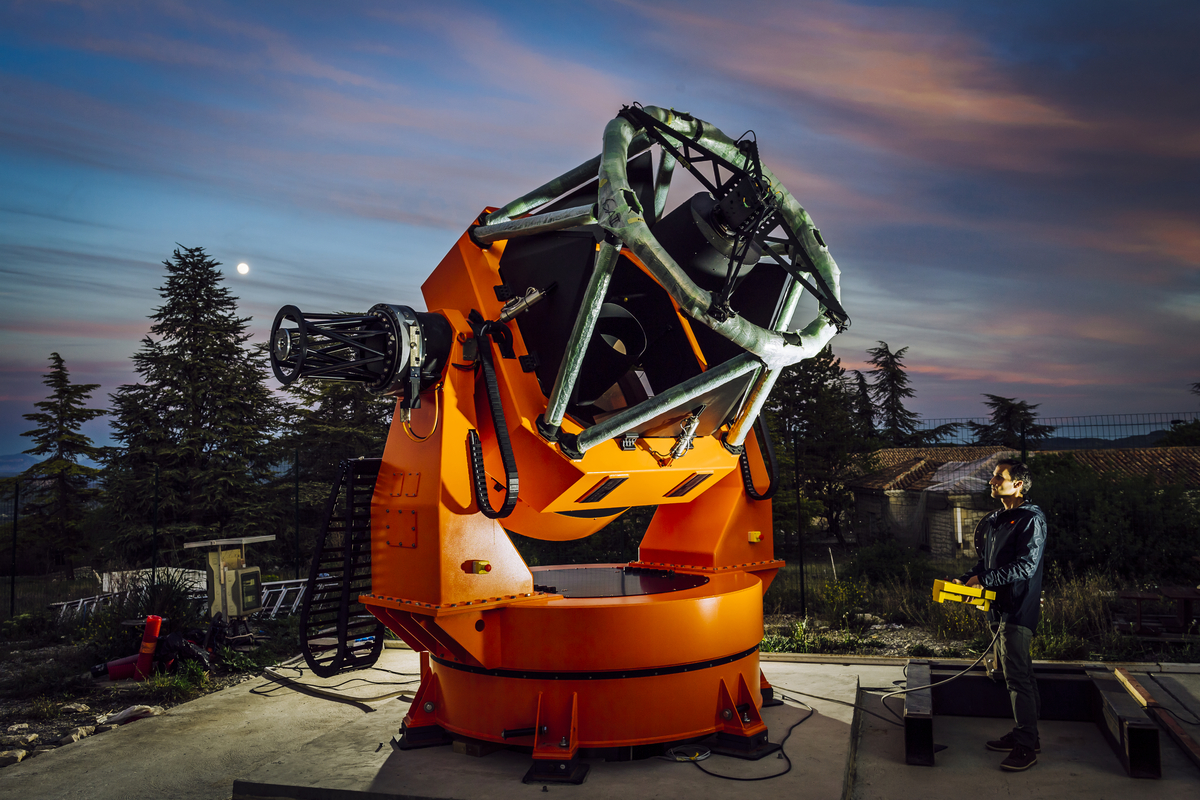

Astronomy is one of the areas the law would aim to protect along with research more generally. The position expressed by the CNRS identifies a number of threats to the quality and viability of astronomical data caused by the proliferation of satellites, particularly of the commercial variety. The visible light trails of satellites, the way they reflect sunlight and directly or indirectly cause interference with radio astronomical waves are all risk factors that are already having a negative effect on scientific observation. Clearly such issues will only continue and increase as satellite constellations grow even more and the whole situation leads Nicolas Arnaud to draw a bleak conclusion. "The proliferation of things that fly around us, that can or will fly, or actually have flown, and also things that are less visible, the invasion of near-Earth space by emissions in all directions – all of this will one day make it impossible for us to do radio astronomy research. That's why the CNRS's position stresses the importance of regulation in our response to the EU Space Law, so that a space can be maintained in which we can continue – notably – to practice science".

As well as science, the CNRS is also campaigning for the preservation of dark and quiet skies. This applies equally to human activities and to other inhabitants of the blue planet. The organisation's campaign makes it clear that the overall increase in the sky's brightness can impact biology and living species, particularly many species' migratory patterns. The CNRS is coordinating the 'dark ecological' network to strive to conserve this biodiversity. Finally, the exponential growth in the number of satellite constellations increases the risk of direct collisions and therefore raises fears about the destruction of scientific instruments that monitor climate indicators and carry out weather modelling. These are of course invaluable from both a scientific and a societal standpoint.

Research - a key stakeholder in the sustainable space of tomorrow

Faced with the brusque arrival on the scene of these new players, the research world is reiterating through this European law that, as Nicolas Arnaud says, it is "a player in the sustainable space of tomorrow" and vital for the competitiveness of the European space sector. To achieve this, extraterrestrial activities need to be protected and the long-term viability of basic research needs to be ensured while reinforcing the budget in this area. The CNRS's positioning document, and more generally the influence exerted by representatives of European research organizations in Brussels, are aimed at ensuring that the voice of research is heard in the next European framework program for research and innovation. This is particularly important given that the work of organisations like the CNRS involves far more than basic research alone. Alain Mermet, director of the Europe & International Department of the institution, views the CNRS as "a real player in New Space" thanks to the fifteen or so start-ups in this field that have emerged from its laboratories. One example is ThrustMe, which designs rocket engines for very small satellites.

The CNRS's positioning document on the Space Law argues in favour of the enhanced integration of research organisations in European space policy to play two roles. Firstly, they could act as guarantors of the quality of space-derived data, ensuring their traceability and processing at a time when "the proliferation of operators is certainly increasing the potential sources of Earth observation data, but not in a way that is supervised by scientists", as Alain Mermet explains, Secondly with the increasing possibility of Man returning to the Moon or even taking the first steps on Mars and the massive development of in-orbit services looming on the horizon, research organisations could take on an advisory role which will require the development of specific interdisciplinary expertise.

This positioning would reinforce Europe's uniqueness in the international space landscape while in no way undermining the competitiveness of European industry. As Nicolas Arnaud observes, "the space data issue permeates the whole economy because the aim is to make data more affordable, better distributed, more available and more adapted to stakeholder requirements". Ultimately, science does not focus on space because it has its head in the stars but because what happens in space necessarily impacts on our lives down here on Earth.